Tom Block was a BAC 1-11 captain and eventually attended recurrent training in a ground school class that I taught. I remember him saying to another pilot just before class first began, "I wonder what they are going to teach us about the BAC 1-11 this time."

Tom has written several novels and is now retired and running a horse ranch in Florida.

When I had experienced pilots in my class, I made it more of a directed conversation, than a lecture. It kept everyone more involved and these folks were actually flying the plane and had real world experience to relate. We could all learn from that.

Although I can't remember what it was, I remember a moment when Tom Block's question was answered. We had touched on a subject that turned on a light for him. I still remember the look on his face. After all, he was a celebrity.

When we started in the simulator for my training, my partner was much lower on the learning curve than I was. He was a smart guy, but had been flying light airplanes for a commuter airline, Cessna 402s. I had been flying this very same simulator for 3 years and flying all the training and check ride profiles. Tom was able to dedicate more attention to my partner.

Pacific Express was having us trained to pass a type rating check ride. Normally, the training is for a first officer (co-pilot) ride, which has fewer requirements than a type rating (captain) ride. PacEx was trying to save money, instead of sending us back for additional training when we upgraded. The company was growing and upgrades were coming after only a year on the seniority list. We both passed, then we moved on to the airplane training.

Since I had not been flying airplanes more than a few hours for the last 4 years, I was having a little more trouble than my partner. The airplane flew differently. I did well enough to pass my airplane check ride, but my confidence was a little shaken moving forward. It was not up to the standards I placed on myself.

This was an extreme example of an axiom I had learned in my flight instructor days. Long layoffs between flying can really make a pilot rusty and it takes time to knock that rust off.

Doreen and I found a small house to rent in Chico on Floral Avenue. It had a "swamp cooler" and a small swimming pool. These would help us deal with the dry heat of summer in Chico. Our landlord, John Bay, and his wife Shirley, were our next door neighbors. Both houses sat on a 10 acre lot. To defray our rental costs, we asked John if we could board horses that belonged to others and he approved.

Chico was the smallest crew base for Pacific Express. San Francisco was the biggest.

The corporate headquarters was located in Chico, probably for the same reason I wanted to be based there. It was much less expensive than San Francisco or Los Angeles. The company had a hangar at the Chico Airport and flew into Chico each evening and out each morning. There were 8 pilots based there, 4 captains, 4 first officers, to fly the planes in and out each day. The plan was to perform maintenance, during the night, that required a hangar.

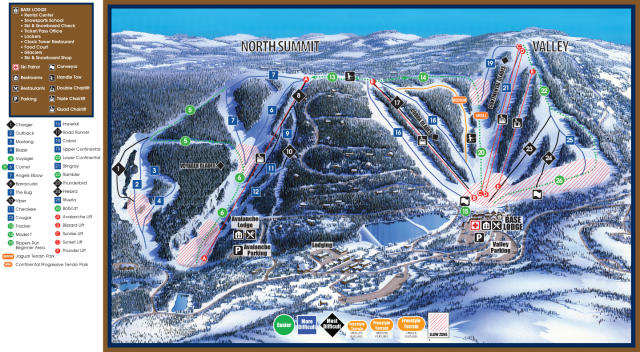

The airline had been flying for nearly a year before I arrived. The route structure changed several times. The picture above shows one example. The big marketing hit among city pairs was supposed to be the one between San Francisco and Palm Springs. Essentially, it was a hub and spoke system in San Francisco, with a smaller hub in Los Angeles. The northernmost cities were Portland, Oregon and Boise Idaho. The southernmost were LA and Palm Springs.

Block time means from when the plane begins moving away from the gate to when it stops moving at a gate. Our average block time in the system was 45 minutes. Our longest block time was one hour 30 minutes, between San Francisco and Palm Springs. We flew as many as 6 legs a day.

The company used an old fashioned, convoluted, complicated and busy weight and balance system, that was done by the first officer. We had to wait until we had the final passenger count, before we could do most of the form. We got that as the main entry door was being closed. It was a process of making numerical entries in a column, doing some grade school math and drawing a line that followed guidelines down through a graph based on the weight and balance envelope of the plane. Each plane had its own numbers to begin with. This was not a very challenging process, except that there was tremendous time pressure to get it done and tremendous accuracy pressure to prevent killing ourselves or getting in trouble with the FAA. At airports where we had jetways, the bell was ringing as it was pulled away. In most cases, the captain had to open his window and throw the form out or place it in something the station had put together to collect it, as we were starting engines and running checklists. I became conditioned, like Pavlov's dogs, to go into a panic when I heard that bell. The FOs rarely got out of their seat during a 6 leg day.

To make matters more challenging, we had scheduling issues. After flying the plane for a few months, the flight department learned that it was burning a lot of fuel if they flew it as fast as it could go. Fuel can be saved by slowing the plane down. We flew it very slowly, compared to the other airlines, 250 knots indicated to climb, cruise and descend. Without getting into the weeds too much with regard to indicated and true airspeed, we were kind of like a moving road block out there for the other airlines. The scheduling challenge arose, because the company published the schedule as if we were flying at the same speeds as the other airlines. This meant that we were behind schedule on the first leg of the day and this was compounded with each subsequent leg.

To make matters worse, the time on the ground was minimal. If there was any kind of glitch in unloading and loading the plane, we added time to our lateness. A maintenance issue would just completely wipe us out. It was a real snowballing problem. We were always trying to avoid additional delays and trying to find ways to speed things up. Lots of pressure. On top of all of that, the old BAC 1-11s we were flying were a maintenance nightmare. They broke, frequently. But, they were pretty.

Chico was the smallest crew base for Pacific Express. San Francisco was the biggest.

The airline had been flying for nearly a year before I arrived. The route structure changed several times. The picture above shows one example. The big marketing hit among city pairs was supposed to be the one between San Francisco and Palm Springs. Essentially, it was a hub and spoke system in San Francisco, with a smaller hub in Los Angeles. The northernmost cities were Portland, Oregon and Boise Idaho. The southernmost were LA and Palm Springs.

Block time means from when the plane begins moving away from the gate to when it stops moving at a gate. Our average block time in the system was 45 minutes. Our longest block time was one hour 30 minutes, between San Francisco and Palm Springs. We flew as many as 6 legs a day.

The company used an old fashioned, convoluted, complicated and busy weight and balance system, that was done by the first officer. We had to wait until we had the final passenger count, before we could do most of the form. We got that as the main entry door was being closed. It was a process of making numerical entries in a column, doing some grade school math and drawing a line that followed guidelines down through a graph based on the weight and balance envelope of the plane. Each plane had its own numbers to begin with. This was not a very challenging process, except that there was tremendous time pressure to get it done and tremendous accuracy pressure to prevent killing ourselves or getting in trouble with the FAA. At airports where we had jetways, the bell was ringing as it was pulled away. In most cases, the captain had to open his window and throw the form out or place it in something the station had put together to collect it, as we were starting engines and running checklists. I became conditioned, like Pavlov's dogs, to go into a panic when I heard that bell. The FOs rarely got out of their seat during a 6 leg day.

To make matters more challenging, we had scheduling issues. After flying the plane for a few months, the flight department learned that it was burning a lot of fuel if they flew it as fast as it could go. Fuel can be saved by slowing the plane down. We flew it very slowly, compared to the other airlines, 250 knots indicated to climb, cruise and descend. Without getting into the weeds too much with regard to indicated and true airspeed, we were kind of like a moving road block out there for the other airlines. The scheduling challenge arose, because the company published the schedule as if we were flying at the same speeds as the other airlines. This meant that we were behind schedule on the first leg of the day and this was compounded with each subsequent leg.

To make matters worse, the time on the ground was minimal. If there was any kind of glitch in unloading and loading the plane, we added time to our lateness. A maintenance issue would just completely wipe us out. It was a real snowballing problem. We were always trying to avoid additional delays and trying to find ways to speed things up. Lots of pressure. On top of all of that, the old BAC 1-11s we were flying were a maintenance nightmare. They broke, frequently. But, they were pretty.