Little brother, Kevin, rode down to Atlanta with me. It was Christmas break. I rented another UHaul trailer, loaded my junk and headed north. Ugh!

I had been enjoying the milder winters. The summers were a little too hot, but I was not crazy about the prospect of living in snow country again. It was the middle of winter, going through the mountains of West Virginia and it was not a flying job.

I spent the quiet time during the drive trying to solve that problem. What could I do to make myself look forward to winter in Pittsburgh?

The answer that kept coming back was skiing. Yeah, I only had a couple encounters with that and they were not enjoyable, but everyone else seemed to be having fun. Perhaps if I could learn how to do it.

Making a financial commitment always helps me focus. I went to Willi's Ski Shop and dropped $500+ on equipment and clothes. That was real money for me in 1980.

But before that, I started my time of employment at USAir on NewYears Eve 1979. I guess I didn't do much that first day. All I can remember is that I had a cold.

I would be working with Jim Quinzi and Doc Watson on the BAC 1-11, a small, British jet. It had been the primary plane of Mohawk Airlines, which merged with Allegheny, which became USAir. The BAC (some people pronounce it Bock, the Brits always say B.A.C.) was a stepchild airplane at USAir. Jim and Doc were mechanics and had gone to the factory school in England when Mohawk first bought the plane. There were a couple other instructors who had gone also, but they had moved on to other planes at USAir. Jim and Doc knew all the nuts and bolts of this plane and would begin my training program.

When I first started flying, Allegheny was the airline I wanted to fly for eventually. My ex-wife worked for them. My friends, Dan and J.B. worked for them. Allegheny was my home town airline and it was now called USAir, which implied they intended to grow the company's system beyond the regional system they had always operated. Pay and benefits were good and it seemed like a good place to hang out until something came along.

Somewhere in all this time, one of my students offered me a job. His company sold large, industrial pumps. He was one of the guys who got all the licenses to fly his Seneca II, but hired me when he was flying employees or customers. He had even taken me on some really cool trips to the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

The Eastern Shore is a place that seemed to have been left behind a little by the passage of time. It was quaint and beautiful. We flew down there to hunt geese on one trip and to go fishing in the Chesapeake Bay on the other. These are examples of the some of the fringe benefits of working at Graham Aviation.

Any way, this guy wanted me to work as a salesman at his company and be available to fly the airplane. There were times during the five years at Butler when I probably would have jumped at that opportunity.

The belief that I would live my dream and become an airline pilot wavered dramatically and the thought of such a corporate job would have been very attractive. However, once I made the decision to get the flight engineer rating, I felt I had to follow through and give it my best shot or regret it for the rest of my life. I explained that to my student, friend and prospective employer and he understood.

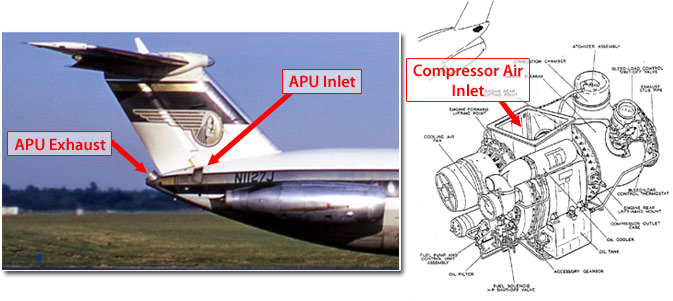

Jim Q. told me to learn one of the airplanes systems at a time. I would start with the Auxiliary Power Unit (APU). This was the small turbine engine mounted in the tail, that drove a generator to provide electrical power and used bleed air from its compressors to provide air conditioning on the ground.

Early on, Jim told the students how we taught the plane. He said that we were going to tell them what we were going to tell them. Then we were going to tell them. We would follow this up by telling them what we told them. Repetition. We reinforced this by having them talk about nearly the entire plane with each of the three of us in the classroom, to get a slightly different perspective and way of describing it from each of us. If I taught the APU yesterday, Jim or Doc would start the next day by going around the classroom asking each student what he or she had learned the previous day. We would do this until we were satisfied that all the important stuff was digested and understood. Then we would have a big overall review just before the written test.

The way we told them what we were going to tell them, was teaching the "origination check list" the first day in class. This was the interior preflight check done by one of the pilots before each sequence of flights. It followed a flow pattern through all the cockpit panels, discussing every light, indicator, switch and control. We had a slide tray all ready to follow that pattern and Jim wanted me to be the primary guy to do that day.

I really enjoyed this. It sped up the learning of the entire plane for me to learn how to do that. I would tell the class that I was about to teach them everything they would ever need to know about the BAC 1-11 in one day, but that they would not be able to remember all of it. We would then spend the next couple weeks going back over all this and discussing it in detail and then reviewing. I think this gave them confidence that they would get it all and would get it well enough to retain it.